With a vast amount of research and writing completed on the subject of Jackie Robinson and the African American foray into the United States’ national pastime, Powers-Beck’s The American Indian Integration of Baseball is a seminal piece of scholarship that shifts the focus away from the injustices thrust upon African Americans and introduces the plight of the Native American ball players. Further, Powers-Beck brings forth multiple views of the historical discourse surrounding the topic. That is, he explores the foundation of Native American baseball through the context of both the Indian industrial schools and by providing narrative biographies of, among others, Charles Bender, Jim Thorpe, and John Meyers – the first three Native Americans to break into the big leagues of the American baseball infrastructure.

Powers-Beck, a professor of English and assistant dean of Graduate Studies at East Tennessee State University, holds both his Ph.D. And M.A. from Indiana University. The American Indian Integration of Baseball is not his first book, having published Writing the Flesh: The Herbet Family Dialogue in 1998. Additionally, Powers-Beck is well credited through his many publications in journals including “A Role New to the Race: A New History of the Nebraska Indians” as found in the Winter 2004 edition of Nebraska History and “Jon Billman’s ‘Indians’ and American Indian Exhibition Baseball, 1897-1945” as found in the book Baseball/Literature/Culture: Essays. The book that is the topic of this review is a highly credible offshoot of Powers-Beck’s preexisting knowledge and work. Lastly, Powers-Beck’s work on this book earned him the 2005 Larry Ritter Book Award, as sponsored by the Deadball Committee and Society for American Baseball Research.

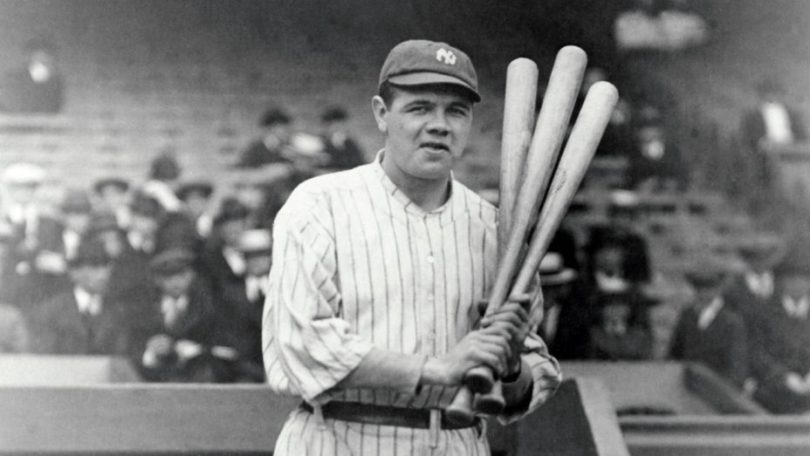

The book, in its physical form, is worth of praise itself. Available as a hardcover, the book provides excellent organization, breaking down the different phases of the integration into further organized chapters. More importantly, however, is the book’s ability to bring the early pioneers of American Indian baseball to life through the use of rare historical illustrations. Rather than using stock images of some of the more well-known American Indian ball players, Powers-Beck did diligent work to locate photos from sources such as the archives of several industrial schools and through the collections of family heirlooms of former players. Further, Powers-Beck includes various charts and tables to assist the understanding of the text and also provides an extensive amount of endnotes and appendixes, the likes of which could constitute a book of their own.

The significance of the book is not in the endnotes and/or appendixes, though. Rather, as mentioned, the book is a true seminal piece that tells the story of the American Indian integration of baseball. While the foremost objective of the text is to conceptualize the history of American Indian integration, which Powers-Beck does beautifully, there is a prominent underlying issue within the book that delves deeper into the discourse than the provided narrative history – the assimilation of the American Indians. While telling the story of integration, Powers-Beck also describes the pressures and hardships encountered by Indians in adjusting to the game and to life in the non-Indian world. In doing so, the author uses the personal writings and other historical documents of those Indians removed from their reservations and placed into the industrial schools. In the two chapters dedicated to the most influential industrial schools of the period, Powers-Beck further strengthens his argument that the industrial schools were used as a United States Government tool of assimilation against the American Indians. Overall, Powers-Beck highlights, with proper documentation and fact, that the American Indian had to battle just as much discrimination and racism as the African Americans did to integrate American baseball.

The breadth of the documentation presented by Powers-Beck is a testament to the accuracy and contemporary “staying power” of the book. Referenced often in the endnotes is a staggering amount of newspapers dating from the mid-1800s to the mid-1900s. It should be noted that the broadsheets being used were not considered the major papers of the era. Rather, Powers-Beck dug deep into the archives of more regional prints, such as the Knoxville Daily Journal and the Bristol (TN) Sentinel. The research, and thus documentation, becomes even more impressive when Powers-Beck entered the chapters dealing with the industrial schools. It is here that much information is pulled from the archives of the Cumberland County (PA) Historical Society. Further, trips to more known archives, such as the United States National Archives and Records Administration, add to the completeness of Powers-Beck’s research and documentation.

Powers-Beck’s portrayal of baseball as a tool of assimilation fits into a larger body of knowledge. While The American Indian Integration of Baseball is the only work of its kind to connect baseball and assimilation, other prominent works have told the story using different scenarios as the lynchpin. Powers-Beck focuses much of his efforts on the Lakota tribes of the Black Hills in South Dakota. The majority of American Indians that were sent to the industrial schools were removed from this tribe and, further, the tribe itself was the victim of the largest criminal act committed in United States history. In order to not wade too deep into the subject, it is recommended that potential readers of Powers-Beck’s book also read Edward Lazarus’ Black Hills, White Justice and Jeffrey Ostler’s The Lakotas and The Black Hills: The Struggle for Sacred Ground. Additionally, Ward Churchill’s From A Native Son: Selected Essays on Indigenism, 1985-1995 provides more insight to the selected tools of assimilation. Finally, Joseph Oxendine’s American Indian Sports Heritage focuses on the sporting practices of various tribes and enters into the discussion of how Indian sporting tradition shifted from recreation to the necessity to defend tribal land and culture from the “white man.” The aforementioned authors all furnish a greater contextual understanding of the issues surrounding the Lakota tribe that Powers-Beck writes of in his work. Reversely, Powers-Beck’s book renders another point of Lakota-U.S. Government contention that Lazarus, et. al describe without the added knowledge of baseball integration and assimilation.

The effectiveness and, more importantly, value of Powers-Beck’s work is a great contribution to the existing body of knowledge on the subject of American Indian assimilation. As previously noted, Powers-Beck details a component of the overarching story that many, if not all, other works seem to cast aside as not important. Previous to Powers-Beck’s book, the amount of attention and research paid to Robinson’s racial integration of baseball vastly, if not completely, overwhelmed the struggles of other races and ethnicities facing the same problem. However, The American Indian Integration of Baseball not only fills in the blanks left by previous baseball research, but opens up more avenues to advance the studies of Indian assimilation and the use of sport as a tool to do so.